Director’s Notes No.5

Heald’s pièce de résistance

South Wall of MoNA’s First Floor Galleries—Charles Laurens Heald (1940-2019), In the Rockies, 1986 - 1987, acrylic on canvas, 16 panels, 72” x 42” (each) - 56 feet long, MoNA Permanent Collection, gift of Charles Laurens and Dana Heald

(Detail) Charles Laurens Heald (1940-2019), In the Rockies, 1986 - 1987, acrylic on canvas, 16 panels, 72” x 42” (each) - 56 feet long, MoNA Permanent Collection, gift of Charles Laurens and Dana Heald

Charles Laurens (Larry) Heald (1940-2019) painted In the Rockies, acrylic on canvas, over a period of two years, 1984-1986. In the Rockies is organized according to the four cardinal directions and spans an improbable 360-degree, or full panoramic, view: left to right, we are presented with a sequence of lakes dressed in skirts of vivid green (west), craggy peaks engulfed by a snow storm and deep dark valleys cut through barren mountain sides (north), a window over plains with lakes lining up as they recede in the distance (east) and as we reach the other end of the painting what appears to be a mountain pass dotted by myriad outcropping red rocks (south). In addition, as we move along the image, the landscape seamlessly registers distance either as close-up views, or as vistas from afar, or finally as a picture captured at quite close range. I should have shared upfront that this is not your typical landscape painting. Heald painted In the Rockies as an opera in four movements: the 16 panels were composed four at a time, using the fourth of the previous set as the starting point for the next set of four. Stretched over 16 canvases, 72" x 42" each, In the Rockies is 56 feet long.

Panoramic view - Cardinal points from left to right - West, North, East, South—Charles Laurens Heald (1940-2019), In the Rockies, 1986 - 1987, acrylic on canvas, 16 panels, 72” x 42” (each) - 56 feet long, MoNA Permanent Collection, gift of Charles Laurens and Dana Heald.

This artwork is a remarkable statement if one considers that it is about 6 inches longer than Monet's largest water lilies painting, the Nymphéas, les deux saules (1914-1926) in the permanent collection of the Musée de L'Orangerie, Paris. It is also more than twice the size of Jackson Pollock's Mural (1943), which stretches nearly twenty feet wide by eight feet high and is the largest painting Pollock ever made. In the Rockies' scale is massive even when compared to the mundane and almost banal size of large things we probably encounter every day: at 56 feet, the painting is 3 feet longer than the trailer of a semi-truck (which, believe it or not, comes at 53 feet) or the length of three SUVs parked in line on the side of the road. It is so long that walking from one end to the other at an average pace (2—2.5 miles per hour) will take us between 15 and 20 seconds. Heald was no stranger to large-size paintings, but In the Rockies is another story, a story of epic proportions.

Claude Monet (1840–1926), Nymphéas, Les Deux Saules, 1914 -1926, oil painting, 78.74” x 669.24” (55.77 feet), Collection of Musée de l'Orangerie, donation of the artist, 1922. Photo by Jean-Pierre Dalbéra

At some point in the mid-eighties, Heald conceived a project (this!) extraordinarily ambitious, arduous, and grandiose. For which he realized scale had to matter. And scale indeed matters!

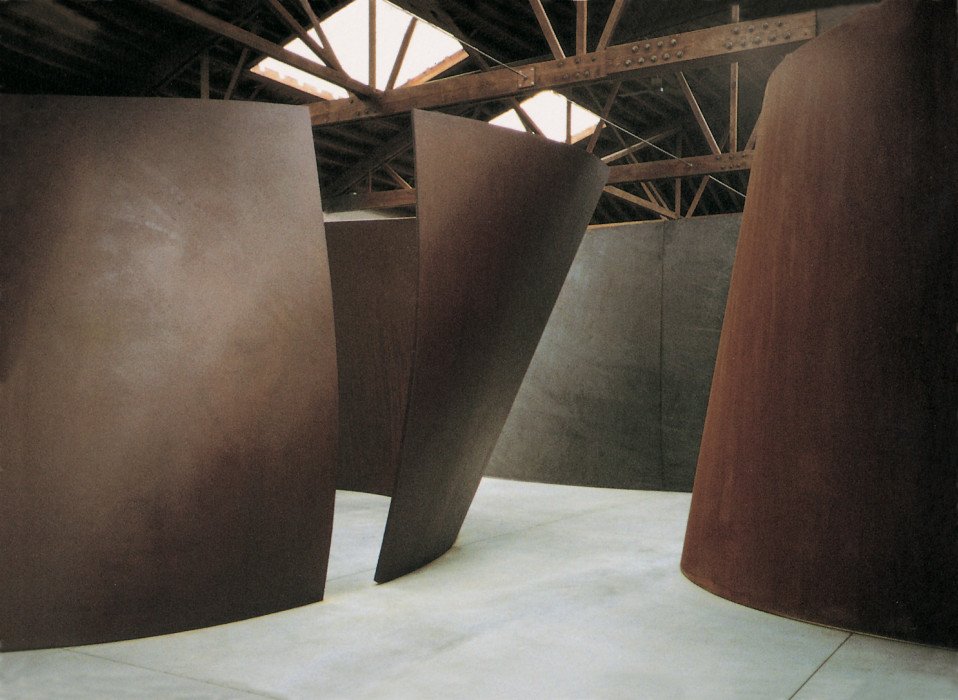

Richard Serra, Torqued Ellipses, installation view, 545 West 22nd Street, New York City. © Richard Serra/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (Source: www.diaart.org)

Think of Richard Serra's Torqued Ellipses COR-TEN sculptures—started by the artist in 1996—which challenge and destabilize viewers' perception of their bodies in relation to space and landscape, often eliciting feelings of awe, disorientation, vulnerability, and unease, leading to fear for one's safety.

Richard Serra, Sequence, 2006, Cor-ten steel, Fisher Collection Loan, Stanford Museum. Photo by Rob Corder

Sequence (2006) at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University achieves exactly this by pushing the viewer who ventures into it to walk under massive leaning steel walls. Serra's investigation into the experience of perception relies on the position that the whole cannot be known at once, only experienced with physical movement and progressively over time, which is what Heald's In the Rockies does. As one sees the painting, one is immediately overcome with a sense of curiosity followed by a surge of awe. As we get closer to the painting, it does not take much to realize the impossibility of panning with the eyes over the entire picture in one look—the horizontal canvas is so long (and the images so detailed) that it cannot be taken in at once. The built-in resistance of the painting to be comprehended in its entirety does not undermine the monumentality of the natural theater of the Rockies Heald captured. On the contrary, it sets a pace, quite literally, for the viewer to do so: yes, we are prevented by its sheer scale from taking in the changing temperatures and atmospheric qualities of the environment, but the painting also asks the viewer to embark on a journey, at their own pace, to enjoy the picture and its richness of natural and artistic features. I should share that the painting is hanging on the gallery's south wall—the only wall that could accommodate it—a wall whose frontal view is blocked by another wall. The possibility of finding a point of view in the galleries from where to admire the whole painting is also denied. All we are left then is to pace ourselves along the painting, now stepping back just enough to admire a section looking at a closer distance, attracted now by a rock that maybe for a moment resembled an animal, now by a dead Engelmann spruce still standing. It is also at a close range that we can see how Heald applied the acrylic paint very thinly in translucent layers, thus building up the texture of the different landscapes and the depth of the topography. Calligraphic marks, often in a darker hue, are often found against lighter backgrounds, adding complexity and character to the terrain and, in my opinion, a whimsical element.

(Detail) Charles Laurens Heald (1940-2019), In the Rockies, 1986 - 1987, acrylic on canvas, 16 panels, 72” x 42” (each) - 56 feet long, MoNA Permanent Collection, gift of Charles Laurens and Dana Heald

(Detail) Charles Laurens Heald (1940-2019), In the Rockies, 1986 - 1987, acrylic on canvas, 16 panels, 72” x 42” (each) - 56 feet long, MoNA Permanent Collection, gift of Charles Laurens and Dana Heald

Is there wildlife In the Rockies? I have searched carefully but to no avail. If you visit MoNA before the end of the month when the exhibition Re Building (in which the work is featured) comes down, I encourage you to carefully scan the surface in the hope of finding bighorn sheep, black bears, marmots, mountain lions, beavers, hares, eagles, ravens or coyotes. If you do find something, please let me know. Nevertheless, there are signs of life: a thread of smoke rises at the bottom of a dark valley, where the shadows of the surmounting peaks have already put out the light of day. It has slowly spread up the valley, gauzy and barely there. The scent of the bonfire blends with the earthy and pleasant smell brought out of the terrain by the rainfalls battering the peaks above. Take this as a hint to find it.

A landscape artist through and through, Heald studied at the University of Washington in Seattle where he received a BA (cum laude) in 1963, and an MFA in painting in 1964. Fresh out of college, Heald was included in "Art Across America" (1965) and the "85th Annual" (1966) at the San Francisco Museum of Art. Heald moved to Skagit Valley, Washington, in 1970. During the next four years, he was included in several important exhibitions, including "American Landscape" at the University of Washington, "Prospect Northwest" and "Skagit Valley Artists" at the Seattle Art Museum. Heald was given a retrospective at the University of Puget Sound, Tacoma, in 1983 and exhibited with the original "Skagit Valley Artists" at the Museum of Northwest Art, La Conner, Washington, in 1992.